A day in the life of an extreme matter scientist

Chemist Ben Ofori-Okai investigates what happens to matter under extreme conditions at microscopic scales to better understand its behavior at massive scales, such as what happens in the Earth’s core.

Ben Ofori-Okai learned the difference between an MD and a PhD at a younger age than most when someone introduced his father, a chemist, as “Dr. Ofori-Okai.”

“I was only 4 years old, but I remember thinking, ‘My dad’s not a doctor. He doesn’t treat people,’” Ofori-Okai says. “That’s when I learned that there was a different kind of doctor: a scientist.”

The idea stuck in his mind, and in high school Ofori-Okai, now a postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory who studies the material properties of warm dense matter, decided to follow in the footsteps of his father into the curious world of STEM.

“It seemed like such an interesting thing to do to make a living out of constantly seeking answers to the unknown,” he says. “When I went to college, I discovered that I wasn’t terrible at chemistry, so I just kept going down that path. Now it’s 12 years later, and I guess I’m a scientist.”

Connecting on a deeper level

At first, Ofori-Okai’s father jokingly warned him not to become a chemist, saying that he’d always be stuck in a lab working with chemicals. But he thinks his dad was just happy that he knew what he wanted to do, and in the end it added a whole new layer to their relationship.

“Since I became a chemist, we’ve been able to have a wider range of conversations than a typical father and son pair might have, just because we share this common ground,” he says. “He’ll ask me very detailed questions about what I’m working on, and I can’t get away with just giving him a quick answer. It allows us to talk on a deeper level.”

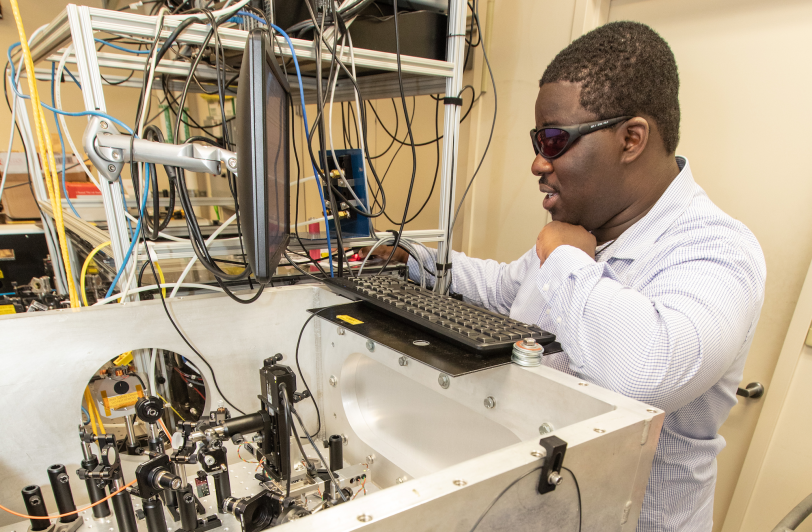

Ofori-Okai started his undergraduate career at Yale, moving on to MIT for his PhD. At SLAC, he’s an experimentalist in the High Energy Density Sciences Division, where he performs experiments at the lab’s Sector-10 laser lab and Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) X-ray laser. He says he spends a lot of time thinking about “how small stuff works, and how that impacts what it does when it’s not so small.” Although, like his father, his training is in chemistry, these days his work is more in the vein of physics, borrowing from areas such as condensed matter and plasma physics.

“A lot of my time is spent staring at really hard problems,” he says. “I love that, as a scientist, I have the freedom and resources to try to solve them. When I don’t figure something out right away, I feel simultaneously bummed out and hopeful that I’ll solve it eventually.”

Extreme conditions

Depending on the day, Ofori-Okai spends time either setting up experiments, collecting and analyzing data or going to meetings to collaborate and brainstorm with colleagues. Often during the day, he finds himself so gripped by these lingering questions that he forgets to eat lunch.

In particular, he investigates what happens to matter when it’s subjected to the extreme pressures and temperatures one might find in the hearts of planets. For instance, by studying how these conditions affect the conductivity of materials in the lab, he hopes to reach a better understanding of how processes in the center of the Earth produce its large magnetic fields.

“You could make the argument that what we’re studying is basic and fundamental,” he says. “But having that understanding is important because it gives you guidance for other problems that need to be solved. Everything is connected to something else, so having that knowledge is a steppingstone to future discoveries and advancements.”

Venturing into the unknown

Ofori-Okai says he loves the freedom that being a scientist allows him to venture into the unknown and add to the fundamental understanding of the world. Growing up, he says, he always had the impression that scientists already had answers to most of the questions one could ask.

“In elementary school, I learned about the layers of the Earth and always thought that we knew about these things directly,” he says. “Years later, I realized that a lot of what we know was discovered indirectly through models and experiments, and that there are still so many unanswered questions remaining. Having the ability to go into the lab and chip away at hidden truths and figure out how they impact the world around us is really cool.”

LCLS is a DOE Office of Science user facility.

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.